HISTORY

"There are two Mustafa Kemals. One is the flesh-and-bone Mustafa Kemal who now stands before you and who will pass away. The other is you, all of you here who will go to the far corners of our land to spread the ideals which must be defended with your lives if necessary. I stand for the nation's dreams, and my life's work is to make them come true." Atatürk stands as one of the world's few historic figures who dedicated their lives totally to their nations. He was born in 1881 (probably in the Spring) in Selanik, then an Ottoman city, now in Greece. His father, Ali Riza, a customs official turned timber merchant, died when Mustafa was still a boy. His mother, Zubeyde, a devout and strong-willed woman, raised him and his sister. First enrolled in a traditional religious school, he soon switched to a modern school. In 1893, he entered a military high school where his mathematics teacher gave him the second name Kemal (meaning "perfection") in recognition of young Mustafa's superior achievement. He was thereafter known as Mustafa Kemal. In 1905, Mustafa Kemal graduated from the Military Academy in Istanbul with the rank of Staff Captain. Posted in Damascus, he started, with several colleagues, a clandestine society called "Homeland and Freedom" to fight against the Sultan's despotism. Mustafa Kemal's career flourished as he won fame and promotions because of his heroism in the farflung corners of the Ottoman Empire, including Albania and Tripoli. He also briefly served as a staff officer in Selanik and Istanbul and as a military attache in Sofia.

When the Dardanelles campaign was launched in 1915, Colonel Mustafa Kemal became a national hero by winning successive vistories and finally repelling the invaders. Promoted to general in 1916, at age 35, he liberated two major provinces in eastern Antalia that year. In the next two years, he served as commander of several Ottoman armies in Palestine and Aleppo, achieving anotherr major victory by stopping the enemy advance at Aleppo. On May 19, 1919, Mustafa Kemal landed in the Black Sea port of Samsun to start the War of Independence. In defiance of the Sultan's government, he rallied a liberation army in Anatolia and convened the Congresses of Erzurum and Sivas which established the basis for the new national effort under his leadership. On April 23, 1920, the Grand National Assembly was inaugurated. Mustafa Kemal was elected to its Presidency. Fighting on many fronts, he led his forces to victory against rebels and invading armies. Following the Turkish triumph at the two major battles at Inonu in Western Turkey, the Grand National Assembly conferred on Mustafa Kemal the title of Commander-in-Chief with the rank of Marshal. At the end of August 1922, the Turkish armies won their ultimate victory. Within a few weeks, the Turkish mainland was completely liberated, the armistice signed, and the rule of the Ottoman dynasty abolished. In July 1923, the national government signed the Lausanne Treaty with Great Britain, France, Greece, Italy and others. In mid-October, Ankara became the capital of the new Turkish State. On October 29, the Republic was proclaimed and Mustafa Kemal Pasha was unanimously elected President of the Republic.

The account of Atatürk's fifteen-year presidency is a saga of dramatic modernization. With indefatigable determination, he created a new political and legal system, abolished the Caliphate and made both government and education secular, gave equal rights to women, changed the alphabet and advanced the arts, sciences, agriculture and industry. In 1934, when the surname law was adopted, the national parliament gave him the name "Atatürk" (Father of Turks). On November 10, 1938, following an illness of a few months, the national liberator and the Father of modern Turkey died. His legacy to his people and to the world endures.

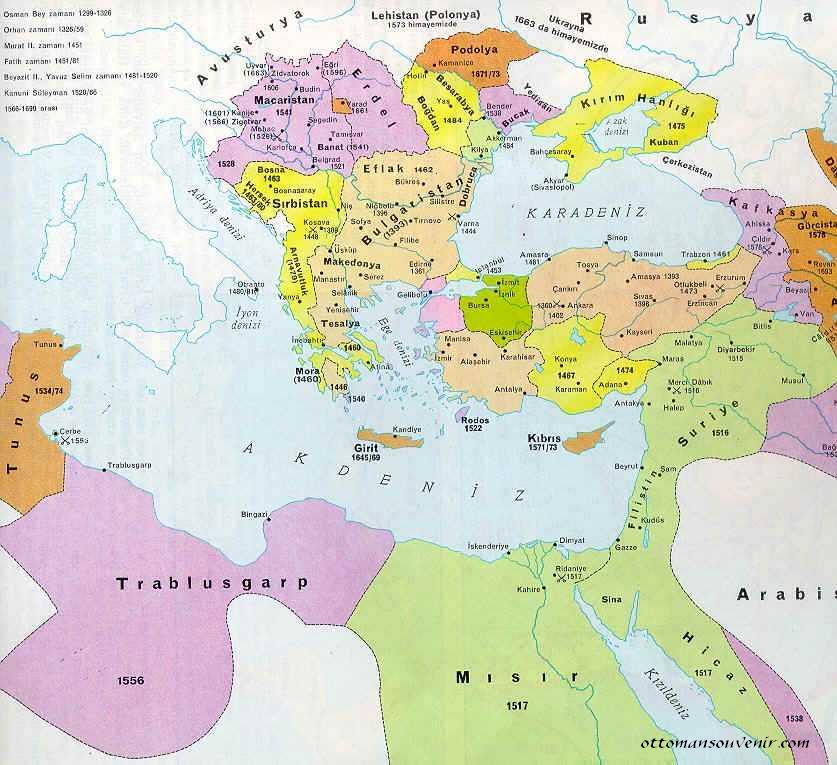

Expansion of the Ottoman Empire The Ottoman Turks were descendants of Turkoman nomads who entered Anatolia in the 11C as mercenary soldiers for the Seljuks. At the end of the 13C, Osman I (from whom the name Ottoman is derived) asserted the independence of his small principality in Sogut near Bursa, which adjoined the decadent Byzantine Empire. Gazis from all over Anatolia hitched themselves to Osman's rising star, following the usual custom of adopting the name of their leader and thus calling themselves Osmanli. Their fight for their religion, holy war, was called gaza, and was intended not to destroy but to subjugate the non-Moslem world.

Within a century the Osman Dynasty had extended its domains into an Empire stretching from the Danube to the Euphrates. In Bosnia, Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia the conquered Christian princes were restored to their lands as vassals, while the subjects were left free to follow their own religions in return for loyalty. The Ottomans accepted submissive local nobility and military commanders into their service, along with their troops, instead of killing them. The empire was temporarily disrupted by the invasion of the Tatar conqueror Timur, who defeated and captured the Ottoman Sultan Bayezit I at the Battle of Ankara (1402). However, Mehmet I (1389-1421), the Restorer, succeeded in reuniting much of the Empire and it was reconstituted by Murat II and Mehmet II. In 1453, Mehmet II conquered Constantinople, the last Byzantine stronghold. During the reigns of Murat II and Mehmet II the devsirme system of recruiting young Christians for conversion to Islam and service in the Ottoman army and administration was developed. The Christians in the army were organized into the elite infantry corps called the Janissaries. Urban families, those with particular skills vital to the local economy, or families with only one son were excluded in this devsirme system. From the poor families' point of view, it was a great chance for their sons to be offered a high level of education especially in the palace which would provide good future prospects. The empire reached its peak in the 16C. Sultan Selim I (r. 1512-20) conquered Egypt and Syria, gained control of the Arabian Peninsula and beat back the Safavid rulers of Iran at the Battle of Caldiran (1514). He was succeeded by Suleyman I (the Magnificent, r. 1520-66), who took Iraq, Hungary and Albania and established Ottoman naval supremacy in the Mediterranean. Suleyman codified and institutionalized the classic structure of the Ottoman state and society, making his dominions into one of the great powers of Europe. Decline of the Ottoman Empire The decline of the empire began late in the 16C. It was caused by a myriad of interdependent factors, among which the most important were the flight of the Turco-Islamic aristocracy and degeneration of the ability and honesty both of the sultans and of their ruling class. The devsirme divided into many political parties and fought for power, manipulated sultans and used the government for their own benefit. Corruption, nepotism, inefficiency and misrule spread. Reform Attempts Sultan Selim III (r. 1789-1807) attempted to reform the Ottoman system by destroying the Janissary corps and replacing it with the Nizam-i Cedit (new order) army modeled after the new military institutions being developed in the West. This attempt so angered the Janissaries and others with a vested interest in the old ways that they overthrew him and massacred most of the reform leaders. Defeats at the hands of Russia and Austria, the success of national revolutions in Serbia and Greece and the rise of the powerful independent Ottoman governor of Egypt, Mohammed Ali, so discredited the Janissaries, however, that Sultan Mahmut II was able to massacre and destroy them in 1826. Mahmut then inaugurated a new series of modern reforms, which involved the abolition of the traditional institutions and their replacement with new ones imported from the West. This affected every area of Ottoman life, not just the military. These reforms were continued and brought to their culmination during the Tanzimat reform era (1839-76) and the reign of Abdulhamit II (1876-1909). The scope of government was extended and centralized as reforms were made in administration, finance, education, justice, economy, communications and army. Financial mismanagement and incompetence, along with national revolts in the Balkans and eastern Anatolia, the French occupation of Algeria and Tunisia, the takeover by the British in Egypt and the Italians in Libya, threatened to end the very existence of the Empire, let alone its reforms. By this time the Ottoman Sultanate was known as the "Sick Man of Europe," and European diplomacy focused on the so-called Eastern Question how to dispose of the Sick Man's territories without upsetting the European balance of power. Abdulhamit II, however, rescued the empire, at least temporarily, by reforming the Ottoman financial system, manipulating the rivalries of the European powers and developing the pan-Islamic and pan-Turkic movements to undermine the empires of his enemies. The sultan granted a constitution and parliament in 1876, but he soon abandoned them and ruled autocratically so as to achieve his objectives as rapidly and efficiently as possible. He became so despotic that liberal opposition arose under the leadership especially in the palace which would provide good future prospects. The empire reached its peak in the 16C. Sultan Selim I (r. 1512-20) conquered Egypt and Syria, gained control of the Arabian Peninsula and beat back the Safavid rulers of Iran at the Battle of Caldiran (1514). He was succeeded by Suleyman I (the Magnificent, r. 1520-66), who took Iraq, Hungary and Albania and established Ottoman naval supremacy in the Mediterranean. Suleyman codified and institutionalized the classic structure of the Ottoman state and society, making his dominions into one of the great powers of Europe. Decline of the Ottoman Empire The decline of the empire began late in the 16C. It was caused by a myriad of interdependent factors, among which the most important were the flight of the Turco-Islamic aristocracy and degeneration of the ability and honesty both of the sultans and of their ruling class. The devsirme divided into many political parties and fought for power, manipulated sultans and used the government for their own benefit. Corruption, nepotism, inefficiency and misrule spread. Reform Attempts

Sultan Selim III (r. 1789-1807) attempted to reform the Ottoman system by destroying the Janissary corps and replacing it with the Nizam-i Cedit (new order) army modeled after the new military institutions being developed in the West. This attempt so angered the Janissaries and others with a vested interest in the old ways that they overthrew him and massacred most of the reform leaders. Defeats at the hands of Russia and Austria, the success of national revolutions in Serbia and Greece and the rise of the powerful independent Ottoman governor of Egypt, Mohammed Ali, so discredited the Janissaries, however, that Sultan Mahmut II was able to massacre and destroy them in 1826.

Mahmut then inaugurated a new series of modern reforms, which involved the abolition of the traditional institutions and their replacement with new ones imported from the West. This affected every area of Ottoman life, not just the military. These reforms were continued and brought to their culmination during the Tanzimat reform era (1839-76) and the reign of Abdulhamit II (1876-1909). The scope of government was extended and centralized as reforms were made in administration, finance, education, justice, economy, communications and army.

Financial mismanagement and incompetence, along with national revolts in the Balkans and eastern Anatolia, the French occupation of Algeria and Tunisia, the takeover by the British in Egypt and the Italians in Libya, threatened to end the very existence of the Empire, let alone its reforms. By this time the Ottoman Sultanate was known as the "Sick Man of Europe," and European diplomacy focused on the so-called Eastern Question how to dispose of the Sick Man's territories without upsetting the European balance of power. Abdulhamit II, however, rescued the empire, at least temporarily, by reforming the Ottoman financial system, manipulating the rivalries of the European powers and developing the pan-Islamic and pan-Turkic movements to undermine the empires of his enemies. The sultan granted a constitution and parliament in 1876, but he soon abandoned them and ruled autocratically so as to achieve his objectives as rapidly and efficiently as possible. He became so despotic that liberal opposition arose under the leadership of the Young Turks, many of whom had to leave the country from Abdulhamit's police.

Overthrow of the Ottoman Empire

In 1908 a revolution led by the Young Turks forced Abdulhamit to restore the parliament and constitution. After a few months of constitutional rule, however, a counterrevolutionary effort to restore the sultan's autocracy led the Young Turks to dethrone Abdulhamit completely in 1909. He was replaced by Mehmet (Resit) V (r. 1909-18), who was only a puppet of those controlling the government.

Rapid modernization continued during the Young Turk era (1908-18), with particular attention given to urbanization, agriculture, industry, communications, secularization of the state and the emancipation of women.

The empire was involved in World War I to take sides with Germany and Austria-Hungary. The defeat of these Central Powers led to the breakup and foreign occupation of the Ottoman Empire.

Return to Main page